Design patterns in python

Many common design patterns are made much simpler or even trivial through the dynamic nature of python

in this lesson, we go through some common design patterns and how they can be implemented in python. we will use class Person as an example wherever appropriate

class Person:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def __repr__(self):

return f"{type(self).__name__}({self.name!r})"

def walk(self):

print(self.name, 'walking')

def run(self):

print(self.name,'running')

def swim(self):

print(self.name,'swimming')

class OlympicRunner(Person):

def run(self):

print(self.name,self.name,"running incredibly fast!")

def show_medals(self):

print(self.name, 'showing my olympic medals')

def train(person):

person.walk()

person.swim()

person.run()

terry = Person('Terry Gilliam')

graham = Person('Graham Chapman')

usainbolt = OlympicRunner('Usain Bolt')

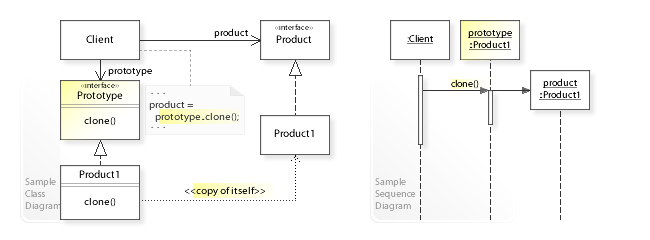

Prototype

The prototype pattern is a creational design pattern in software development. It is used when the type of objects to create is determined by a prototypical instance, which is cloned to produce new objects. Wikipedia

in python implementing this pattern is trivial, since we can easily clone any object regardless of its type

from copy import deepcopy as clone

def simulate_training(person):

simulated_person = clone(person)

simulated_person.name += ' after training'

return simulated_person

trained_usainbolt = simulate_training(usainbolt)

print(usainbolt)

print(trained_usainbolt)

trained_terry = simulate_training(terry)

print(terry)

print(trained_terry)

Singleton

the singleton pattern is a software design pattern that restricts the instantiation of a class to one “single” instance. This is useful when exactly one object is needed to coordinate actions across the system. Wikipedia

The singleton pattern is when we want to have just one object from a particular class.

Many of the complications with implementing singletons in different languages arise from intricacies of making sure that constructing the object or destroying the object can be done safely

this safety is taken care for us by python’s modules. creating an object in a module ensures that all its dependant modules are already loaded so it can be safely constructed. deconstruction is also trivial due to garbage collection.

lastly, to ensure that no further objects can be created from a class, we only need to redefine its __new__ method

here’s sample code to illustrate all this:

#

# module:

# singleton.py

#

def make_singleton(class_):

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

raise Exception('class', cls.__name__, 'is a singleton')

class_.__new__ = __new__

#

# module:

# earth.py

#

from singleton import make_singleton

class HomePlanet:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def __repr__(self):

return f'HomePlanet({self.name})'

earth = HomePlanet('earth')

make_singleton(HomePlanet)

from earth import earth, HomePlanet

print(earth)

# we can't make another instance of HomePlanet

try:

HomePlanet('mars')

except Exception as ex:

print("we only have one home planet, can't make more", ex)

Proxy

See definition of the proxy pattern at wikipedia

What problems can the Proxy design pattern solve?

- The access to an object should be controlled.

- Additional functionality should be provided when accessing an object.

Possible usage scenarios

-

Remote proxy - In distributed object communication, a local object represents a remote object that resides in a different process or machine

-

Virtual/Lazy proxy - In place of a complex or heavy object, a proxy that loads the actual information on demand

-

Protection proxy - A protection proxy might be used to control access to a resource based on access rights.

Python example

We show a completely dynamic implementation of a proxy, that has no knowledge about the object it is proxiying

import inspect

class ProxyExample:

"""

show that we can discover and act upon any call to proxied object functions,

or any access to proxied object attributes

"""

def __init__(self, obj):

self.obj = obj

def __getattr__(self, name):

obj = self.obj

attr = getattr(obj, name)

print(f'accessing {obj}.{name}')

if inspect.isfunction(attr) or inspect.ismethod(attr):

def callable_proxy(*args, **kwargs):

print(f'calling {obj}.{name}() with args:{args} and kwargs:{kwargs}')

result = attr(*args, **kwargs)

return result

return callable_proxy

else:

return attr

# make a proxy to usain bolt

usain_proxy = ProxyExample(usainbolt)

# now every action taken is logged

usain_proxy.name

usain_proxy.run()

Composition

Sometimes we want to model ‘has-a’ relationship instead of an ‘is-a’ relations. for instance, we can say a person has (or composes) arms, legs, a face, a head and eyes.

the composition patterns allows the composing object to behave as if all the abilities of the composed object

lets see an example. the ‘magic’ of how this works is available in the composition.py module in this repository

# import a local module named composition that holds all the magic

from composition import Composition

class Arms:

def up(self):

print("I raised my arms")

class Legs:

def up(self):

print("I raised my legs")

class Eyes:

def close(self):

print("I closed my eyes")

class Face:

def __init__(self):

Composition.compose(self, Eyes())

def smile(self):

print('I smiled')

def __getattr__(self, arg):

return Composition.get_composed_attr(self, arg, super())

class Head:

def __init__(self):

Composition.compose(self, Face())

def balance(self):

print("I shook my head")

def __getattr__(self, arg):

return Composition.get_composed_attr(self, arg, super())

class Person:

def __init__(self):

Composition.compose(self, Arms())

Composition.compose(self, Legs())

Composition.compose(self, Head())

def __getattr__(self, arg):

return Composition.get_composed_attr(self, arg, super())

person = Person()

person.up_arms() # # calls person.arms.up()

person.up_legs() # calls person.legs.up()

person.balance_head() # calls person.head.balance()

person.smile_face() # calls person.head.face.smile()

person.close_eyes() # calls person.head.face.eyes.close()

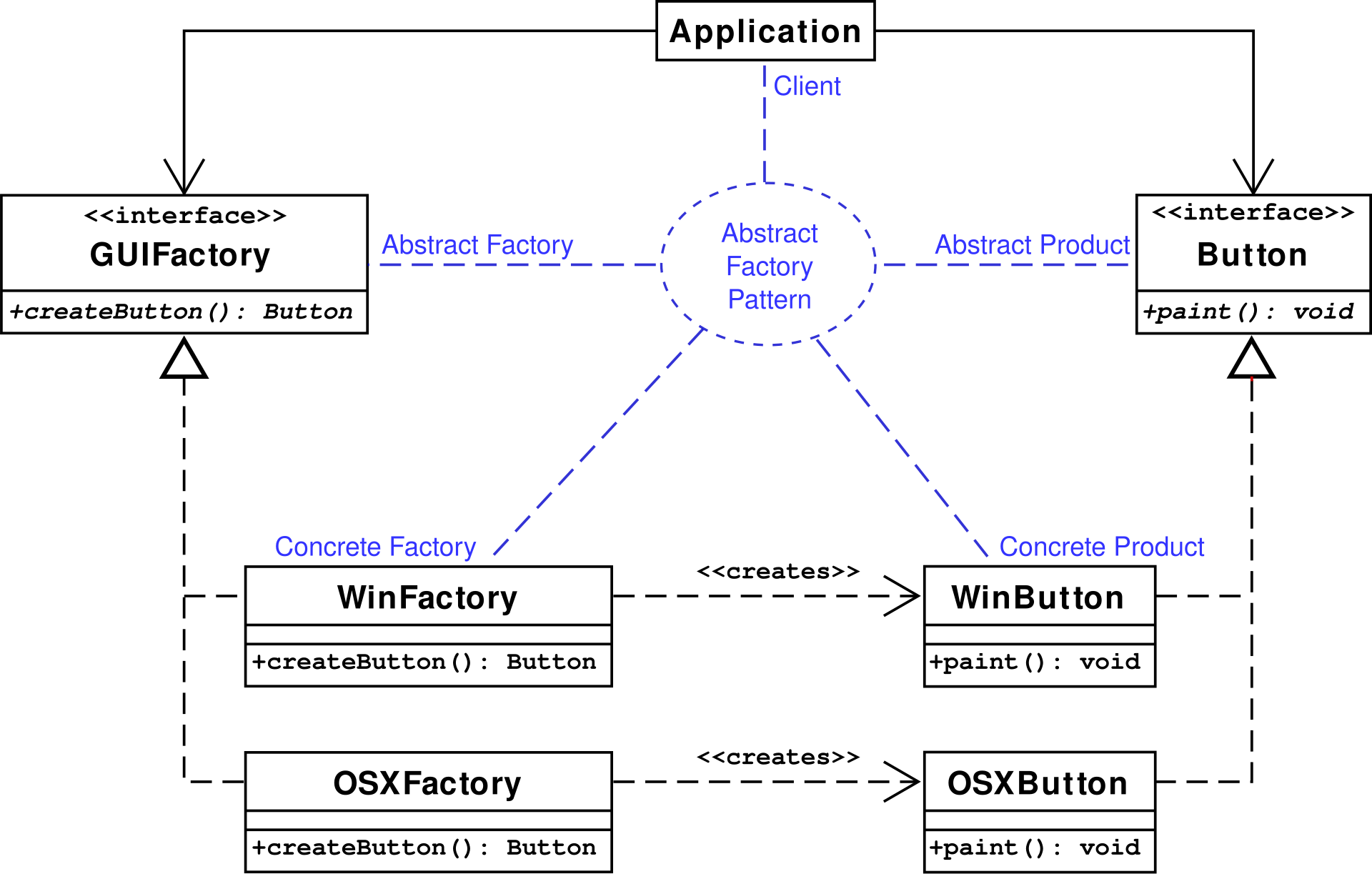

Abstract Factory

“Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes.”

Example with cross platform GUI

Implementation using the buttons themselves as factories

pretty trivial, notice that the abstact Button already

provides a default implementation of create_button that works for all the derived types in the example

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Button(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def paint(self):

pass

@classmethod

def create_button(concrete_class):

return concrete_class()

class LinuxButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return "Render a button in a Linux style"

class WindowsButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return "Render a button in a Windows style"

class MacOSButton(Button):

def paint(self):

return "Render a button in a MacOS style"

def get_factory(platform):

factories = { 'linux' : LinuxButton(), 'osx' : MacOSButton(), 'win' : WindowsButton()}

return factories[platform

]

factory = get_factory('linux')

button = factory.create_button()

result = button.paint()

print(result)

Resource Acquisition Is Initialization (RAII)

Resource acquisition is initialization (RAII)[1] is a programming idiom[2] used in several object-oriented languages to describe a particular language behavior. In RAII, holding a resource is a class invariant, and is tied to object lifetime: resource allocation (or acquisition) is done during object creation (specifically initialization), by the constructor, while resource deallocation (release) is done during object destruction (specifically finalization), by the destructor. Thus the resource is guaranteed to be held between when initialization finishes and finalization starts (holding the resources is a class invariant), and to be held only when the object is alive. Thus if there are no object leaks, there are no resource leaks. Wikipedia

- We will implement RAII using the

withstatement. - with the help of the

contextlibmodule, its easy to create a safe context manager object for any class

import contextlib

class ExpensiveObject:

def start(self):

print('setting up', self)

def close(self):

print('tearing down', self)

def use(self):

print('using', self)

def __repr__(self):

return "ExpensiveObject"

@contextlib.contextmanager

def open_expensive_object():

obj = ExpensiveObject()

obj.start()

try:

yield obj

finally:

obj.close()

with open_expensive_object() as obj:

obj.use()