Logging in python

Logging is a handy tool in a programmer’s toolbox. It can helps develop a better understanding of the flow of a program and discover scenarios that you might not even have thought of while developing. This is doubly true for non-interactive programs, such as batch processing, servers and calculations running in a cluster.

Logs provide developers with an ability to monitor in detail the progress and errors and flow of information in an application. They often store information, for example usernames or IP addresses accessed the application. If an error occurs, logs can provide more insights than a stack trace by telling you what the state of the program was before it arrived at the line of code where the error occurred.

By logging useful data from the right places, you can find and fix errors easily but also use the data to analyze the performance of the application to plan for scaling or look at usage patterns to plan for marketing.

Credits

This lesson incorporates content from the following resources:

- logly: exceptional logging of exceptions in python

- electricmonk: understanding pythons logging module

- django deconstructed: django and python logging in plain english

- RealPython: Logging in python

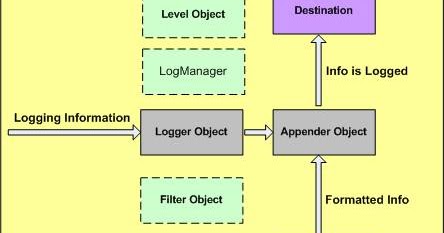

The logging funnel

The key to understanding how logging works is knowing that it encourages you to log a lot of data, and then gives multiple mechanisms for filtering out that data. It’s similar to a funnel. Lots of data goes in, but most of it gets filtered out before leaving the system as formatted logs

Why does it work this way? Because that leads to simple application code (just log everything!) that stays the same from environment to environment. Filters can then be configured via settings and config files to match the environment. If you’re debugging locally you may want to filter nothing out and create log records of everything. But on production, you only want to know about errors, in which case you can add more filters (i.e. the funnel gets much more narrow).

|

|

Historical background: Log4J

Logging in python is heavily influenced by a logging paradigm popularized by the log4j library for the Java language. log4j offered a framework built on Hierarchial loggers and a root logger, log levels, appenders, and layout objects, and inspired ports in many other languages, including: C/C++, Perl, JavaScript, C# etc

|

|

|

|

Basics

The Logging Module

The logging module in Python is a ready-to-use and powerful module that is designed to meet the needs of beginners as well as enterprise teams. It is used by most of the third-party Python libraries, so you can integrate your log messages with the ones from those libraries to produce a homogeneous log for your application.

Adding logging to your Python program is as easy as this:

import logging

With the logging module imported, you can use something called a “logger” to log messages that you want to see. By default, there are 5 standard levels indicating the severity of events. Each has a corresponding method that can be used to log events at that level of severity. The defined levels, in order of increasing severity, are the following:

- DEBUG

- INFO

- WARNING

- ERROR

- CRITICAL

The logging module provides you with a default logger that allows you to get started without needing to do much configuration. The corresponding methods for each level can be called as shown in the following example:

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger('my_logger')

logging.basicConfig()

logger.debug('This is my 😂 debug message ')

logger.info('This is my 💜 info message ')

logger.warning('This is my 🤔 warning message ')

logger.error('This is my error 😱message ')

logger.critical('This is my 😭 critical message ')

Lets unpack what’s happening here:

- The output lines start with

WARNING/ERROR/CRITICALwhich are the severility levels we used - followed by

my_logger:- this is the name of the logger We’re logging through (Loggers are discussed in detail in later sections.) - followed by our custom error message

This format, which shows the level, name, and message separated by a colon (:), is the default output format that can be configured to include things like timestamp, line number, and other details.

Notice that the

debug()andinfo()messages didn’t get logged. This is because, by default, the logging module logs the messages with a severity level of WARNING or above. You can change that by configuring the logging module to log events of all levels if you want. You can also define your own severity levels by changing configurations, but it is generally not recommended as it can cause confusion with logs of some third-party libraries that you might be using.

Basic Configurations

You can use the basicConfig(**kwargs) method to configure the root logger (more on that later):

“You will notice that the logging module breaks PEP8 styleguide and uses camelCase naming conventions. This is because it was adopted from Log4j, a logging utility in Java. It is a known issue in the package but by the time it was decided to add it to the standard library, it had already been adopted by users and changing it to meet PEP8 requirements would cause backwards compatibility issues.” (Source)

Some of the commonly used parameters for basicConfig() are the following:

level: The root logger will be set to the specified severity level.filename: This specifies the file.filemode: If filename is given, the file is opened in this mode. The default is a, which means append.format: This is the format of the log message.

Example: By using the level parameter, you can set what level of log messages you want to record. This can be done by passing one of the constants available in the class, and this would enable all logging calls at or above that level to be logged. Here’s an example:

%%python

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger('my_logger')

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.DEBUG # allow DEBUG level messages to pass through the logger

)

logging.debug('This WILL get logged')

All events at or above DEBUG level will now get logged.

It should be noted that usually calling

basicConfig()to configure the root logger works only if the root logger has not been configured before. Basically, this function should usually only be called once.

You can customize the root logger even further by using more parameters for basicConfig(), which can be found here.

The default setting in basicConfig() is to set the logger to write to the console in the following format:

ERROR:root:This is an error message

Logging Variable Data

In most cases, you would want to include dynamic information from your application in the logs. You have seen that the logging methods take a string as an argument, and it might seem natural to format a string with variable data in a separate line and pass it to the log method. But this can actually be done directly by using a format string for the message and appending the variable data as arguments. Here’s an example (using Python’s older C-style % string formatting):

%%python

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger('my_logger')

logging.basicConfig()

name = 'Aviad'

logger.error('A person called "%s" raised an error', name)

The arguments passed to the method would be included as variable data in the message.

If you’re unfamiliar with the %-based style, the f-strings introduced in Python 3.6 are an awesome way to format strings as they can help keep the formatting short and easy to read:

%%python

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger('my_logger')

logging.basicConfig()

name = 'Aviad'

logger.error(f'A person called "{name}" raised an error')

Note: when using f-string formatting, pass just one fully formatted string to the logger functions

Configurations

Logging to file

from this point on, we’re going to do quite a bit of usage of the Path object to handle files and folders, so lets import it

from pathlib import Path

basicConfig()can be used to configure logging to output to a file rather than the console. filename and filemode parameters are used, and you can decide the format of the message using format. The following example shows the usage of all three:

%%python

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger('my_logger')

logging.basicConfig(

filename='app.log', # write to this file

filemode='a', # open in append mode

format='%(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s'

)

logging.warning('This will get logged to a file')

now logging does not write to console anymore, but instead to the specified file:

print(Path('app.log').read_text())

Formatting the Output

While you can pass any variable that can be represented as a string from your program as a message to your logs, there are some basic elements that are already a part of the LogRecord and can be easily added to the output format. If you want to log the process ID along with the level and message, you can do something like this:

%%python

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger('my_logger')

logging.basicConfig(format='ID:%(process)d - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

logger.warning('This Warning contains the process ID of the process who logged it')

format= can take a string with LogRecord attributes in any arrangement you like. The entire list of available attributes can be found here.

Here’s another example where you can add the date and time info:

%%python

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger('my_logger')

logging.basicConfig(format='%(asctime)s - %(message)s', level=logging.INFO)

logger.info('This message has a date/time timestamp')

%(asctime)s adds the time of creation of the LogRecord. The format can be changed using the datefmt attribute, which uses the same formatting language as the formatting functions in the datetime module, such as time.strftime():

%%python

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger('my_logger')

logging.basicConfig(format='%(asctime)s - %(message)s', datefmt='%d-%b-%y %H:%M:%S')

logger.warning('Date looks different for this message')

You can find the date/time formatting guide here.

Anatomy of logging module: Classes and Functions

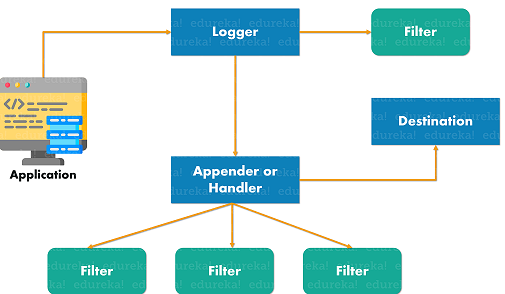

So far, we have seen the default logger named root, which is used by the logging module whenever its functions are called directly like this: logging.debug(). You can (and should) define your own logger by creating an object of the Logger class, especially if your application has multiple modules. Let’s have a look at some of the classes and functions in the module.

The most commonly used classes defined in the logging module are the following:

-

Logger: This is the class whose objects will be used in the application code directly to call the functions. -

LogRecord: Loggers automatically create LogRecord objects that have all the information related to the event being logged, like the name of the logger, the function, the line number, the message, and more. -

Handler: Handlers send the LogRecord to the required output destination, like the console or a file. Handler is a base for subclasses like StreamHandler, FileHandler, SMTPHandler, HTTPHandler, and more. These subclasses send the logging outputs to corresponding destinations, like sys.stdout or a disk file. -

Formatter: This is where you specify the format of the output by specifying a string format that lists out the attributes that the output should contain.

we’ll talk more in depth about all of these below, right now we’re keeping to the basics.

Out of these, we mostly deal directly with the objects of the Logger class, which are instantiated using the module-level function logging.getLogger(name). Multiple calls to getLogger() with the same name will return a reference to the same Logger object, which saves us from passing the logger objects to every part where it’s needed.

Here’s an example:

%%python

import logging

logging.basicConfig() # setup basic formatting for the root logger

logger = logging.getLogger('example_logger')

logger.warning('This is a warning')

This creates a custom logger named example_logger.

it inherits the the handler and formatting from the root logger, is why it outputs to console, and uses the same formatting as the root logger

“It is recommended that we use module-level loggers by passing

__name__as the name parameter togetLogger()to create a logger object as the name of the logger itself would tell us from where the events are being logged.__name__is a special built-in variable in Python which evaluates to the name of the current module.” (Source)

Using Handlers

Handlers come into the picture when you want to configure your own loggers and send the logs to multiple places when they are generated. Handlers send the log messages to configured destinations like the standard output stream or a file or over HTTP or to your email via SMTP.

A logger that you create can have more than one handler, which means you can set it up to be saved to a log file and also send it over email.

Like loggers, you can also set the severity level in handlers. This is useful if you want to set multiple handlers for the same logger but want different severity levels for each of them. For example, you may want logs with level WARNING and above to be logged to the console, but everything with level ERROR and above should also be saved to a file.

For Here’s a program that does configures handlers with code:

NOTE: as we will see later in this lesson, people usually use configuration files rather than code, to setup loggers/handlers.

%%python

import logging

# Create a custom logger

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.propagate = False # do not pass logs to the default logger

# Create handlers

c_handler = logging.StreamHandler()

f_handler = logging.FileHandler('file.log', mode='w')

c_handler.setLevel(logging.WARNING)

f_handler.setLevel(logging.ERROR)

# Create formatters and add it to handlers

c_format = logging.Formatter('%(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

f_format = logging.Formatter('%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

c_handler.setFormatter(c_format)

f_handler.setFormatter(f_format)

# Add handlers to the logger

logger.addHandler(c_handler)

logger.addHandler(f_handler)

logger.warning('This is a warning')

logger.error('This is an error')

Here, logger.warning() is creating a LogRecord that holds all the information of the event and passing it to all the Handlers that it has: c_handler and f_handler.

c_handleris aStreamHandlerwith levelWARNINGand takes the info from the LogRecord to generate an output in the format specified and prints it to the console.f_handleris aFileHandlerwith levelERROR, and it ignores this LogRecord as its level is WARNING.

When logger.error() is called, c_handler behaves exactly as before, and f_handler gets a LogRecord at the level of ERROR, so it proceeds to generate an output just like c_handler, but instead of printing it to console, it writes it to the specified file:

print(open('file.log').read())

Using configuration files

While it is possible to configure logging as shown above using the module and class functions, it is more flexible and useful to use configuration files for this

We can configure logging by creating a config file or a dictionary and loading it using fileConfig() or dictConfig() respectively. These are useful in case you want to change your logging configuration in a running application.

Here’s an example file configuration:

%%file example.conf

[loggers]

keys=root,sampleLogger

[handlers]

keys=consoleHandler

[formatters]

keys=sampleFormatter

[logger_root]

level=DEBUG

handlers=consoleHandler

[logger_sampleLogger]

level=DEBUG

handlers=consoleHandler

qualname=sampleLogger

propagate=0

[handler_consoleHandler]

class=StreamHandler

level=DEBUG

formatter=sampleFormatter

args=(sys.stdout,)

[formatter_sampleFormatter]

format=%(asctime)s | %(levelname)-7s | %(name)s - %(message)s

In the above file, there are two loggers, one handler, and one formatter. After their names are defined, they are configured by adding the words logger, handler, and formatter before their names separated by an underscore.

To load this config file, you have to use fileConfig():

%%python

import logging

import logging.config

logging.config.fileConfig(fname='example.conf', disable_existing_loggers=False)

# Get the logger specified in the file

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.debug('This is a debug message')

The path of the config file is passed as a parameter to the fileConfig() method, and the disable_existing_loggers parameter is used to keep or disable the loggers that are present when the function is called. It defaults to True if not mentioned.

Here’s the same configuration in a YAML format for the dictionary approach:

%%file config.yaml

version: 1

disable_existing_loggers: False

formatters:

simple:

format: '%(asctime)s | %(levelname)-7s | %(name)s - %(message)s'

handlers:

console:

class: logging.StreamHandler

level: DEBUG

formatter: simple

stream: ext://sys.stdout

loggers:

sampleLogger:

level: DEBUG

handlers: [console]

propagate: no

root:

level: DEBUG

handlers: [console]

%%python

import logging

import logging.config

import yaml

with open('config.yaml', 'r') as f:

config = yaml.safe_load(f.read())

logging.config.dictConfig(config)

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.debug('This is a debug message')

the YAML configuration is usually considered cleaner and more preferrable, although the INI-style configuration has been around longer and is perhaps more well known.

Understanding logging in-depth

Loggers

Loggers are the application-level interface to the logging system. A system may have multiple different loggers, each with their own name and rules.

it is good common practice for developers to have a logger per module

question: what would be the name of the logger in this file?

# file: project/moduleA/submoduleX/x3.py import logging logger = logging.getLogger(__name__) logger.info('module initialized')

answer:

the variable __name__ would expand to "project.moduleA.submoduleX.x3" which would be the name of the logger.

output from this program might look like this:

INFO | project.moduleA.submoduleX.x3 - module initialized

thus, when using __name__ as the name of the logger, the name helps us localize a log message to a particular file in our project.

Logger hierarchy

Loggers have a hierarchy. That is, you can create individual loggers and each logger has a parent. At the top of the hierarchy is the root logger. For instance, we could have the following loggers:

myapp

myapp.ui

myapp.ui.edit

These can be created by asking a parent logger for a new child logger:

log_myapp = logging.getLogger("myapp")

log_myapp_ui = log_myapp.getChild("ui")

print(log_myapp_ui.name) # 'myapp.ui'

print(log_myapp_ui.parent.name) # 'myapp'

Or you can (and should!) use dot notation:

log_myapp_ui = logging.getLogger("myapp.ui")

print(log_myapp_ui.name) # 'myapp.ui'

print(log_myapp_ui.parent.name) # 'myapp'

You should use the dot notation generally.

One thing that’s not immediately clear is that the logger names don’t include the root logger. In actuality, the logger hierarchy looks like this:

root.myapp

root.myapp.ui

root.myapp.ui.edit

More on the root logger in a bit.

inheritance

To understand how the logger hierachy is useful, we need to understand how loggers are structured. If you look at most functional apps you won’t see any specific logger names getting looked up in application code. You’ll see something similar to the following:

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

__name__ is a built-in Python variable that evaluates to the current module. So in the module project/app/tests, __name__ will evaluate to project.app.tests. That doesn’t mean that the project has explicitly defined a logger named project.app.tests. This is where inheritance comes into the picture.

Python loggers are organized in a parent-child structure with a hierarchy similar to module namespacing. Every application has a main logger that is never (or should never be) used directly. Child loggers point back to parent loggers, which eventually point to the main logger. Names are defined using dot-notation, so the name parent_logger.child_logger denotes a child_logger which “inherits” from a logger named parent_logger.

The child can inherit a log level from the parent, and if we look up a logger that hasn’t explicitly been defined in the logging configuration then logging will create that logger and move up the inheritance tree until one is explicitly defined. The new logger will then inherit that logger’s log-level. So if project.app.tests isn’t defined, logging will check if project.app is defined and use that log-level. If that isn’t defined it will try project. If this still isn’t defined then the root logger will be used.

Benefits of the parent-child architecture:

- General behavior can be added to parent loggers and specific behavior can be added to child loggers.

- Naming and relationships follow the structure that Python already uses for imports, so we don’t need a new mental model.

- It allows us to use module-specific loggers without explicitly configuring them.

Propagation

If we create a new logger dynamically at runtime then that logger won’t have any handlers of its own. It also doesn’t inherit them from its parent. So how does that LogRecord get to a handler?

This problem is solved via propagation. Propagation means passing a log from a child logger to a parent logger’s handlers, which is the default behavior. This means that a LogRecord created by child_logger will first get sent to child_logger’s handlers and then if child_logger.propagate == True it will get passed to the parent logger. The parent logger will then bypass its own filters and send the LogRecord directly to its handlers. If parent_logger.propagate == True this passing will continue until the logger reaches the root logger, or until an ancestor has propagate set to False.

A common design that takes advantage of this hierarchy involves only adding handlers to the root or project-level logger and then adding filters to the application’s child loggers. Module-level loggers are then responsible for what gets logged but the decision of where to send the final LogRecord is controlled at the root-level.

Propagation is useful because, without it, a module-level logger that doesn’t have it’s own handlers wouldn’t actually do anything with the logs it creates. Because of propagation, we can create a new module, lookup the logger for that specific module via the __name__ variable, and immediately have a new logger that inherits a log-level and propagates its logs up to its parent’s handlers.

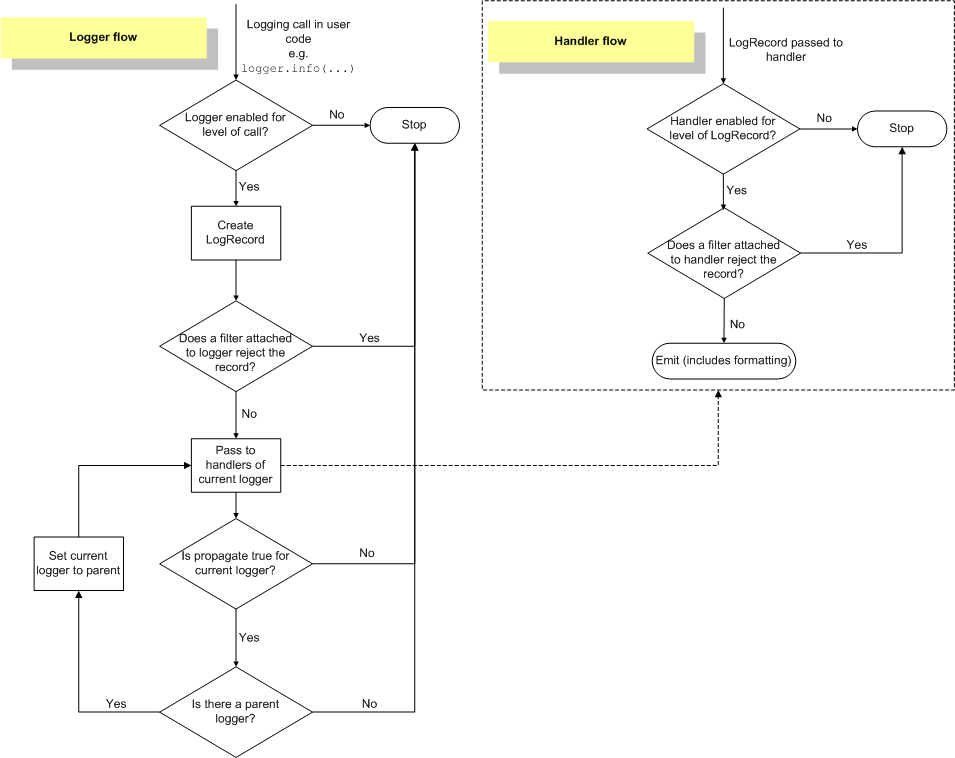

Log levels and message propagation

Each logger can have a log level. When you send a message to a logger, you specify the log level of the message. If the level matches, the message is then propagated up the hierarchy of loggers. One of the biggest misconceptions I had was that I thought each logger checked the level of the message and if it the level of the message is lower or equal, the logger’s handler would be invoked. This is not true!

What happens instead is that the level of the message is only checked by the logger you give the message to. If the message’s level is lower or equal to the logger’s, the message is propagated up the hierarchy, but none of the other loggers will check the level! They’ll simply invoke their handlers.

%%python

import logging

log_myapp = logging.getLogger("myapp")

log_myapp_ui = logging.getLogger("myapp.ui")

logging.basicConfig()

log_myapp.setLevel(logging.ERROR)

log_myapp_ui.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

log_myapp_ui.debug('test')

In the example above, the root logger has a handler that prints the message. Even though the “log_myapp” handler has a level of ERROR, the DEBUG message is still propagated to to the root logger. This image (from the python logging docs) shows why:

As you can see, when giving a message to a logger, the logger checks the level. After that, the level on the loggers is no longer checked and all handlers in the entire chain are invoked, regardless of level. Note that you can set levels on handlers as well. This is useful if you want to, for example, create a debugging log file but only show warnings and errors on the console.

It’s also worth noting that by default, loggers have a level of 0. This means they use the log level of the first parent logger that has an actual level set. This is determined at message-time, not when the logger is created.

The root logger

The logging tutorial for Python explains that to configure logging, you can use basicConfig():

logging.basicConfig(filename='example.log',level=logging.DEBUG)

It’s not immediately obvious, but what this does is configure the root logger. Doing this may cause some counter-intuitive behaviour, because it causes debugging output for all loggers in your program, including every library that uses logging.

Some modules, like the famous

requestsmodule uses logging. This is why the requests module suddenly starts outputting debug information when you configure the root logger.

In general, your program or library shouldn’t log directly against the root logger. Instead configure a specific “main” logger for your program and put all the other loggers under that logger. This way, you can toggle logging for your specific program on and off by setting the level of the main logger. If you’re still interested in debugging information for all the libraries you’re using, feel free to configure the root logger.

There are more pitfalls when it comes to the root logger. If you call any of the module-level logging methods, the root logger is automatically configured in the background for you. This goes completely against Python’s “explicit is better than implicit” rule:

%%python

import logging

logging.warning("uhoh")

In the example above, I never configured a handler. It was done automatically. And on the root handler no less. This will cause all kinds of logging output from libraries you might not want. So don’t use the logging.warning(), logging.error() and other module-level methods. Always log against a specific logger instance you got with logging.getLogger().

Debugging logging problems

When I run into weird logging problems such as no output, or double lines, I generally put the following debugging code at the point where I’m logging the message.

log_to_debug = logging.getLogger("myapp.ui.edit")

while log_to_debug is not None:

print("level: %s, name: %s (%x), handlers: %s" % (

log_to_debug.level,

log_to_debug.name,

id(log_to_debug),

log_to_debug.handlers))

log_to_debug = log_to_debug.parent

which outputs:

level: 0, name: myapp.ui.edit, handlers: []

level: 0, name: myapp.ui, handlers: []

level: 0, name: myapp, handlers: []

level: 30, name: root, handlers: []

From this output it becomes obvious that all loggers use a level of 30, since their log levels are 0, which means the look up the hierarchy for the first logger with a non-zero level. I’ve also not configured any handlers. If I was seeing double output, it’s probably because there is more than one handler configured.

HANDLERS

Handlers answer the question “now that we have a log, where should we send it?” It could go to a file, to the console, get sent as an email, or other possible destinations. The exact behavior could differ depending on context as well. While on your local computer you may want the logs to go to the console so it’s easier to debug, if your code is in production you’ll want a more robust logging setup.

To allow different behaviors, a single logger can send a LogRecord to multiple different handlers, each with their own rules for how to handle the log. setting this up usually happens through configuration

Summary

-

When you log a message, the level is only checked at the logger you logged the message against. If it passes, every handler on every logger up the hierarchy is called, regardless of that logger’s level.

-

By default, loggers have a level of 0. This means they use the log level of the first parent logger that has an actual level set. This is determined at message-time, not when the logger is created.

-

Don’t log directly against the root logger. That means: no logging.basicConfig() and no usage of module-level loggers such as logging.warning(), as they have unintended side-effects.

-

Create a uniquely named top-level logger for your application / library and put all child loggers under that logger. Configure a handler for output on the top-level logger for your application. Don’t configure a level on your loggers, so that you can set a level at any point in the hierarchy and get logging output at that level for all underlying loggers. Note that this is an appropriate strategy for how I usually structure my programs. It might not be for you.

-

The easiest way that’s usually correct is to use name as the logger name: log = logging.getLogger(name). This uses the module hierarchy as the name, which is generally what you want.

-

Read the entire logging HOWTO and specifically the Advanced Logging Tutorial, because it really should be called “logging basics”.

Exceptional logging of exceptions in Python

Exceptions happen. And as developers, we simply have to deal with them. Even when writing software to help us find burritos.

Wait, I’m getting ahead of myself… we’ll come back to that. As I was saying: How we deal with exceptions depends on the language. And for software operating at scale, logging is one of the most powerful, valuable tools we have for dealing with error conditions. Let’s look at some ways these work together.

The “Big Tarp” Pattern

We’re going to start at one extreme:

try:

main_loop()

except Exception:

logger.exception("Fatal error in main loop")

This is a broad catch-all. It is suitable for some code path where you know the block of code (i.e, main_loop()) can raise a number of exceptions you may not anticipate. And rather than allow the program to terminate, you decide it’s preferable to log the error information, and continue from there.

The magic here is with exception method. (logger is your application’s logger object—something that was returned from logging.getLogger(), for example.) This wonderful method captures the full stack trace in the context of the except block, and writes it in full.

Note that you don’t have to pass the exception object here. You do pass a message string. This will log the full stack trace, but prepend a line with your message. So the multiline message that shows up in your log might look like this:

Fatal error in main loop

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "bigtarp.py", line 14, in

main_loop()

File "bigtarp.py", line 9, in main_loop

print(foo(x))

File "bigtarp.py", line 4, in foo

return 10 // n

ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero

The details of the stack trace don’t matter—this is a toy example that illustrates a grown-up solution to a real world problem. Just notice that the first line is the message you passed to logger.exception(), and the subsequent lines are the full stack trace, including the exception type (ZeroDivisionError in this case). It will catch and log any kind of error in this way.

By default, logger.exception uses the log level of ERROR. Alternatively, you can use the regular logging methods— logger.debug(), logger.info(), logger.warn(), etc.—and pass the exc_info parameter, setting it to True:

while True:

try:

main_loop()

except Exception:

logger.error("Fatal error in main loop", exc_info=True)

Setting exc_info to True will cause the logging to include the full stack trace…. exactly like logger.exception() does. The only difference is that you can easily change the log level to something other than error: Just replace logger.error with logger.warning, for example.

Fun fact: The Big Tarp pattern has an almost diabolical counterpart, which you’ll read about below.

The “Pinpoint” Pattern

Now let’s look at the other extreme. Imagine you are working with the OpenBurrito SDK, a library solving the crucial problem of finding a late-night burrito joint near your current location. Suppose it has a function called find_burrito_joints() that normally returns a list of suitable restaurants. But under certain rare circumstances, it may raise an exception called BurritoCriteriaConflict.

from openburrito import find_burrito_joints, BurritoCriteriaConflict

# "criteria" is an object defining the kind of burritos you want.

try:

places = find_burrito_joints(criteria)

except BurritoCriteriaConflict as err:

logger.warn("Cannot resolve conflicting burrito criteria: {}".format(err.message))

places = list()

The pattern here is to optimistically execute some code—the call to find_burrito_joints(), in this case—within a try block. In the event a specific exception type is raised, you log a message, deal with the situation, and move on.

The key difference is the except clause. With the Big Tarp, you’re basically catching and logging any possible exception. With Pinpoint, you are catching a very specific exception type, which has semantic relevance at that particular place in the code.

Notice also, that I use logger.warn() rather than logger.exception(). In other words, I log a message at a particular severity instead of logging the whole stack trace.

Why am I throwing away the stack trace information? Because it is not as useful in this context, where I’m catching a specific exception type, which has a clear meaning in the logic of the code. For example, in this snippet:

characters = {"hero": "Homer", "villain": "Mr. Burns"}

# Insert some code here that may or may not add a key called

# "sidekick" to the characters dictionary.

try:

sidekick = characters["sidekick"]

except KeyError:

sidekick = "Milhouse"

Here, the KeyError is not just any error. When it is raised, that means a specific situation has occurred—namely, there is no “sidekick” role defined in my cast of characters, so I must fall back to a default. Filling up the log with a stack trace is not going to be useful in this kind of situation. And that is where you will use Pinpoint.

The “Transformer” Pattern

Here, you are catching an exception, logging it, then raising a different exception. First, here’s how it works in Python 3:

try:

something()

except SomeError as err:

logger.warn("...")

raise DifferentError() from err

(That turns out to have big implications. More on that in a moment.) You will want to use this pattern when an exception may be raised that does not map well to the logic of your application. This often occurs around library boundaries.

For example, imagine you are using the openburrito SDK for your killer app that lets people find late-night burrito joints. The find_burrito_joints() function may raise BurritoCriteriaConflict if we’re being too picky. This is the API exposed by the SDK, but it does not conveniently map to the higher-level logic of your application. A better fit at this point of the code is an exception you defined, called NoMatchingRestaurants.

In this situation, you will apply the pattern like this (for Python 3):

from myexceptions import NoMatchingRestaurants

try:

places = find_burrito_joints(criteria)

except BurritoCriteriaConflict as err:

logger.warn("Cannot resolve conflicting burrito criteria: {}".format(err.message))

raise NoMatchingRestaurants(criteria) from err

This causes a single line of output in your log, and triggers a new exception. If never caught, that exception’s error output looks like this:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "transformerB3.py", line 8, in

places = find_burrito_joints(criteria)

File "/Users/amax/python-exception-logging-patterns/openburrito.py", line 7, in find_burrito_joints

raise BurritoCriteriaConflict

openburrito.BurritoCriteriaConflict

The above exception was the direct cause of the following exception:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "transformerB3.py", line 11, in

raise NoMatchingRestaurants(criteria) from err

myexceptions.NoMatchingRestaurants: {'region': 'Chiapas'}

Now this is interesting. The output includes the stack trace for NoMatchingRestaurants. And it reports the instigating BurritoCriteriaConflict as well… clearly specifying which was the original.

In Python 3, exceptions can be chained. The raise ... from ... syntax provides this. When you say raise NoMatchingRestaurants(criteria) from err, that raises an exception of typeNoMatchingRestaurants. This raised exception has an attribute named __cause__, whose value is the instigating exception. Python 3 makes use of this internally when reporting the error information.

The “Message and Raise” Pattern

In this pattern, you log that an exception occurs at a particular point, but then allow it to propagate and be handled at a higher level:

try:

something()

except SomeError:

logger.warn("...")

raise

You are not actually handling the exception. You are just temporarily interrupting the flow to log an event. You will do this when you specifically have a higher-level handler for the error, and want to fall back on that, yet also want to log that the error occurred, or the meaning of it, at a certain place in the code.

This may be most useful in troubleshooting—when you are getting an exception, but trying to better understand the calling context. You can interject this logging statement to provide useful information, and even safely deploy to production if you need to observe the results under realistic conditions.

The “Cryptic Message” Antipattern

Now we’ll turn our attention to some anti-patterns… things you should not do in your code.

try:

something()

except Exception:

logger.error("...")

Suppose you or someone on your team writes this code, and then six months later, you see a funny message in your log. Something like:

ERROR: something bad happened

Now I hope and pray that you will not see the words “something bad happened” in your actual log. However, the actual log text you see may be just as baffling. What do you do next?

Well, the first thing is to figure out where in the code base this vague message is being logged. If you are lucky, you will be able to quickly grep through the code and find exactly one possibility. If you are not lucky, you may find the log message in several completely different code paths. Which will leave you with several questions:

Which one of them is triggering the error? Or is it several of them? Or ALL of them? Which entry in the log corresponds to which place? Sometimes, however, it’s not even possible to grep or search through the code to find where it is happening, because the log text is being generated. Consider:

what = "something"

quality = "bad"

event = "happened"

logger.error("%s %s %s", what, quality, event) How would you even search for that? You may not even think of it, unless you searched for the full phrase first and got no hits. And if you did get a hit, it could easily be a false positive.

The ideal solution is to pass the exc_info argument:

try:

something()

except Exception:

logger.error("something bad happened", exc_info=True)

When you do this, a full stack trace is included in the application logs. This tells you exactly what line in what file is causing the problem, who invoked it, et cetera… all the information you need to start debugging.

The Most Diabolical Python Antipattern

If I ever see you do this one, I will come to your house to confiscate your computers, then hack into your github account and delete all your repos:

try:

something()

except Exception:

pass

I refer to this as “The Most Diabolical Python Antipattern.” Notice how this not only fails to give you any useful exception information. It also manages to completely hide the fact that anything is wrong in the first place. You may never even know you mistyped a variable name—yes, this actually masks NameError—until you get paged at 2 a.m. because production is broken, in a way that takes you until dawn to figure out, because all possible troubleshooting information is being suppressed.

Just don’t do it. If you feel like you simply must catch and ignore all errors, at least throw a big tarp under it (i.e. use logger.exception() instead of pass).

Example

Lets create an example project with the following structure:

project/

/-- moduleA/

/-- a1.py

/-- submoduleX/

/-- x1.py

/-- x2.py

/-- moduleB/

/-- b1.py

and lets imagine we want to apply the following rules:

- all logs with level WARNING and above should go to the console

- all logs from moduleA (or its submodules) with level ERROR and above should go to file

moduleA.errors.log - all logs from submoduleX with level INFO and above should go to file

submoduleX.info.log - all logs from submoduleX.x2 with level DEBUG and above should go to file

x2.debug.log - all logs from moduleB.b1 with level DEBUG and above should ONLY go to

b1.logand not to any other place

With logging, this requires no special coding, and is relatively easy to configure:

%%file project/project.yaml

version: 1

disable_existing_loggers: False

formatters:

simple:

format: '%(asctime)s | %(levelname)-7s | %(name)-30s - %(message)s'

handlers:

console:

class: logging.StreamHandler

level: DEBUG

formatter: simple

stream: ext://sys.stdout

moduleA:

class: logging.FileHandler

formatter: simple

filename: 'project/moduleA.errors.log'

submoduleX:

class: logging.FileHandler

formatter: simple

filename: 'project/moduleA.submoduleX.info.log'

x2:

class: logging.FileHandler

formatter: simple

filename: 'project/moduleA.submoduleX.x2.debug.log'

b1:

class: logging.FileHandler

formatter: simple

filename: 'project/moduleB.b1.debug.log'

loggers:

project.moduleA:

level: ERROR

handlers: [moduleA]

project.moduleA.submoduleX:

level: INFO

handlers: [submoduleX]

project.moduleA.submoduleX.x2:

level: DEBUG

handlers: [x2]

project.moduleB.b1:

level: DEBUG

handlers: [b1]

propagate: False

root:

level: WARNING

handlers: [console]

Now lets create the example code files for our project:

from pathlib import Path

example_code = """

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def do_unimportant_thing():

logger.debug('this information is for debugging')

def do_something():

logger.info('doing something')

def warn_about_something():

logger.warn('something could be wrong')

def some_error():

logger.error('there seems to be an error')

"""

project_files = [

'project/moduleA/a1.py',

'project/moduleA/submoduleX/x1.py',

'project/moduleA/submoduleX/x2.py',

'project/moduleB/b1.py',

]

for path in [Path(f) for f in project_files]:

path.parent.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

path.write_text(example_code)

print('Created', path)

and here’s the test program which exercises all the methods of all the modules in our example project.

the program also reads the project.yaml configuration file, and without writing code, routes the logs according to all the rules we wrote in the config file

%%python

import logging

import logging.config

import project.moduleA.a1 as a1

import project.moduleA.submoduleX.x1 as x1

import project.moduleA.submoduleX.x2 as x2

import project.moduleB.b1 as b1

import yaml

from pathlib import Path

config = yaml.safe_load(Path('project/project.yaml').read_text())

logging.config.dictConfig(config)

for module in [a1, x1, x2, b1]:

module.do_unimportant_thing()

module.do_something()

module.warn_about_something()

module.some_error()

You can read through the generated log files and convince yourself that indeed all the fules have been followed

for f in [f for f in Path('project/').iterdir() if f.is_file()]:

print(f.lstat().st_size, 'bytes', '\t', f)